Table of Contents

- Introduction

- How to Harvest the Break-Fix Annuity

- How to Profit from Product Upgrades

- Rescue a Failed Product Launch with Upgrades

Introduction

For established capital equipment companies, the installed base can produce thirty percent or more of the revenue and profit. This significant business deserves as much attention as the new systems business. Complex capital equipment requires constant care and feeding. Throughout its life, it is going to need service, parts, and upgrades. Nobody is in a better position to profit from this need than the original equipment manufacturer.

How to Harvest the Break-Fix Annuity

When capital equipment breaks down, it requires fixing. This cycle of breaking and fixing creates the break-fix annuity for capital equipment suppliers. The components of the break-fix annuity include:

- Replacement and consumable parts

- Software bug fixes

- Repair and maintenance services

You can sum up the break-fix portion of the aftermarket business as all those things your customer pays you for to keep the system running the way you promised when you originally sold it to them. Your customers hate this. Their view is that they are paying you for your failures. As a result, they are highly motivated to reduce or avoid break-fix costs. They will:

- Seek second-source parts suppliers.

- Refurbish instead of replacing parts.

- Design and manufacture parts themselves.

- Skip preventative maintenance.

- Work around a failure to avoid taking the system down.

- Service their own equipment.

- Negotiate parts and service pricing along with system purchases.

The Two Things Customers Value

Break-fix parts and services create value for your customers by:

- Minimizing downtime.

- Lowering repair costs.

To secure your break-fix annuity, you need to be your customer’s best option for delivering on these two value drivers.

Let us try an example. Suppose you supply a certain type of manufacturing equipment that uses a valve to control the process it performs. This valve is a high-wear, high-cost item that requires replacement every three months. It sounds like a perfect break-fix annuity opportunity. Except that your customer does not have to buy this valve from you. It is an off-the-shelf part available from several suppliers.

So, you ask engineering, “Is there some way to force customers to buy this valve from us?” Engineering answers the call and delivers. They design and patent an adapter that sits between the valve and your equipment. On the valve side, the adaptor is welded. On the equipment side, the adapter is attached with a clever twist-lock connector.

You are thrilled. Only valves with this welded adapter will fit your machine. Your patent ensures that the welded adapter valve is only available from you. You have locked in your valve-related, break-fix annuity.

But what you have done amounts to protectionism. Your adapter did not create any new value for the customer. All your proprietary adapter does is force the customer to buy an otherwise readily available part from you, probably at a higher price. Customers will rightfully rebel. You can expect them to:

- Figure out how to work around your patent.

- Ignore your patent, gambling that you will not sue your customer.

- Withhold new equipment orders, payments, references, etc. until you stop the extortion.

- Switch to a competitor the next time they need new equipment.

Do not view your installed base as a captive market that you can force to buy from you. Nothing you do will stop your customers’ relentless pursuit of the best solutions to reduce downtime and lower costs. You may get away with protectionist strategies in the short term, but eventually market forces will prevail.

Instead, approach your break-fix business just as you do your equipment business. Namely, provide more value to your customers than their alternatives. The protectionist, welded-adapter-valve strategy in the previous example did just the opposite. Contrast that with a strategy where engineering developed and patented a valve that lasts six months instead of three. And you priced it at one and a half times the price of the three-month valves from other suppliers. Your new valve lowers customers’ downtime and costs. As a result, you will secure your valve-related, break-fix annuity without harming your customer relationships or future equipment sales.

Look beyond the Obvious Value Drivers

To further secure your break-fix annuity, look beyond the better-parts-at-a-fair-price strategy to provide value. See the list below for some other ways that you can help your customers reduce downtime and lower the cost of repairs.

- Train technical support personnel to send customers regular updates on open issues, even when there is no meaningful progress to report. When customers know that you have not forgotten them, they will not waste time following up.

- Sponsor a users’ group in which users can get together to share best-known methods.

- Develop and send a regular newsletter to all your system users with tips to lower downtime and reduce costs. You can also encourage subscribers to contribute articles.

- Include with every service call a complimentary system audit to ensure there is not a latent issue festering that could lead to unplanned downtime.

- Create automatic ordering and stocking services for consumable parts.

- Generate a formal report for the customer every time you perform a service. Meet with the customer to review the report to ensure that you have completed the service to her satisfaction.

- If a service requires the customer to return defective or worn parts, provide return packaging, including pre-paid shipping.

- Pre-package maintenance and repair kits, including pre-sorted hardware and implementation procedures.

All the above add value, and as a result, each reduces the probability that your customers will look elsewhere for their break-fix help.

Strive for Defect-Free Service

As a consumer, you have likely experienced how a defect-free strategy affects break-fix-services buying behavior. It is the primary strategy employed by new-car dealerships. If you take your car to the dealer for service, you know you are paying a premium. But you do not mind. You know the manufacturer has certified the technicians. They have the right tools. They will inspect for other issues or recalls. Any parts you need are in stock. In short, they will fix your car fast and correctly every time. The repair may cost a little more, but the quick turnaround, one-attempt-and-done experience is well worth it. The confidence you have in the dealer’s ability to deliver defect-free service is why you do not take your car to the independent garage down the street.

However, consider what you would do if a new-car dealer failed to deliver on the defect-free-service promise. You would start experimenting with alternate service providers. If you fail your customers, they will do the same thing.

As the original equipment provider, your customers expect you to be in the best position to deliver defect-free service. Your customers depend on you to keep their systems operating so that they can keep their businesses running. They place their trust in you. Any failure on your part will break that trust. Unfortunately, there are a lot of ways to fail, including:

- Defective parts

- Wrong parts

- Parts out of stock

- Shipping damage

- Late parts delivery

- Repair or maintenance execution errors

- Slow help-line response

- Faulty recovery after maintenance

- Inaccurate invoicing

You do not want to give your customers any reason to look elsewhere for their break-fix parts and services. Therefore, you need the processes and infrastructure that will prevent failures. This can include:

- A closed-loop quality assurance process to ensure defect-free parts

- Extending the quality assurance process to include order processing and shipping activities

- Parts logistics systems that ensure that the right parts are in the right place at the right time

- Robust training and certification for service engineers to ensure they perform maintenance and repair procedures correctly every time

- Effective call center infrastructure, including clear escalation procedures to ensure prompt and accurate responses to customer support requests

The secret to securing your installed base’s break-fix annuity is not that complicated. Just deliver on the customers’ value drivers better than their alternatives without fail.

How to Profit from Product Upgrades

In your break-fix services business, customers pay you to keep the systems running per their original specifications. In the upgrades business, they pay you to make their systems exceed the original specifications. While customers hate paying for break-fix services, they will jump at any opportunity to extend the capability of the systems they have already purchased.

Upgrades extend the life of your customers’ capital investment and create tremendous value for them. Therefore, it is also one of the best profit opportunities for you. Upgrades have a compelling value proposition, no direct competition, and high profit margins.

For many types of capital equipment, the acquisition cost is the single biggest driver of the total cost of ownership. Therefore, your customers want to avoid buying new equipment. Anytime they can extend their existing equipment to the next-generation technology or improve its productivity is an opportunity to avoid new equipment acquisition costs. Sometimes customers even demand to see upgrade roadmaps before they make system purchases.

As the original equipment manufacturer, you are usually the only one who can provide these upgrades. Upgrading the productivity or process capability of complex equipment requires a complete knowledge of its hardware, controls, and software. That creates a significant barrier to entry for a third party. Without direct competition to drive prices down to minimum acceptable margins, you can achieve prices anchored to an upgrade’s full market value.

Value, Not Cost Determines Upgrade Pricing

Meet Max, EquipCo’s product manager extraordinaire. He just learned that the service organization is about to launch a system throughput improvement upgrade. Max met with the service manager in charge of the launch, who told him:

- 500 fielded systems were eligible for the upgrade.

- The original systems could process 100 units per hour and were sold for $4M each.

- The upgrade improves system throughput by 25 percent.

- The upgrade cost of goods sold is $25K.

“Wow! Sounds like a gold mine. How much are we selling the upgrade for?” Max asked.

The service manager replied, “To hit my budget this year, I need to get a 50% gross margin. So, the price is $50K.”

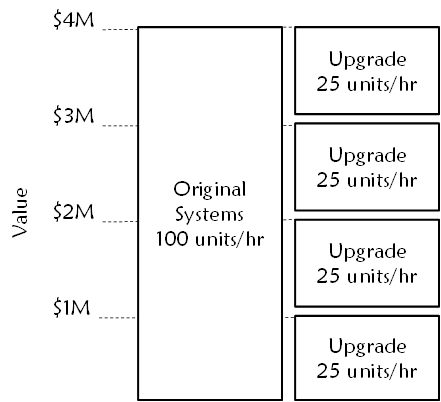

That was not the gold mine Max had in mind. His mental image looked more like the one in Figure 55.

“Hmmm,” Max said, “from what you’ve told me, I’d bet each upgrade is worth about $1M to our customers.”

To which the service manager snapped, “Don’t go messing with my pricing. I know what I’m doing. Remember, this thing only costs $25K. I’m happy with a $50K price, and so is my boss.”

Max thought, “If my hunch is right, we were about to leave a ton of money on the table.” So, Max went back to his office and sent an email to the company’s head of sales describing the upgrade and asking how much he thought EquipCo could get for it.

The head of sales wrote back, “Most of the factories housing the upgradable systems are full. Our customers are four-wall constrained. Expanding by adding new systems is not an option. Purchasing four upgrades is like getting a new $4M system without having to expand the facility. I suggest we list it at $600K. That is a compelling value for our customers, and I imagine an incredible profit opportunity for us.”

Protect New System Sales and Pricing with Upgrades

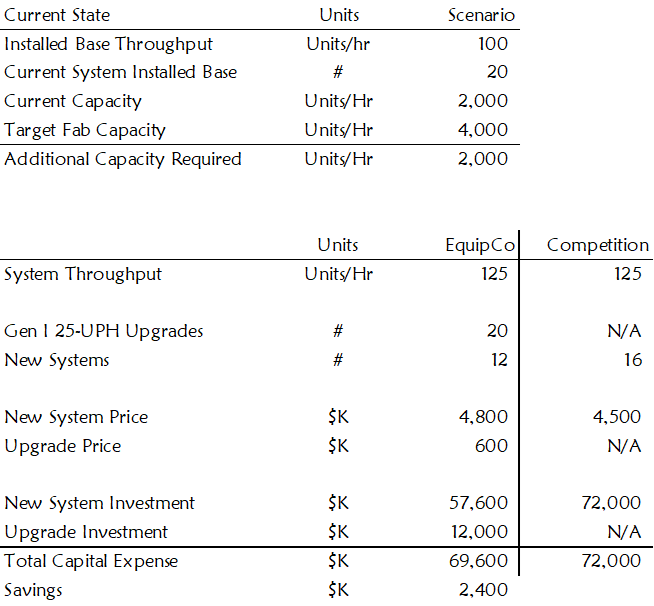

In this example, one of EquipCo’s customers has an installed base of twenty Generation I, 100-unit-per-hour systems. EquipCo has since introduced Generation II of that same machine. This new machine can process 125 units per hour. This customer’s business is expanding, and he now needs an additional 2,000 units per hour of production capacity. Do the math, and you get a need for sixteen Generation II machines.

EquipCo wants to keep this customer and establish a $4.8M selling price for its Generation II machines. But a competitor has emerged that will sell 125-unit-per-hour systems for $4.5M each. The competition’s proposal for sixteen systems is $72M.

Max, the product manager, inserts himself into the sales strategy discussion. “You can defend our installed base and shut this competitor out by linking system upgrades to the new systems’ sale. Look at this,” he says as he distributes the handout shown in Table 23.

| Price Each ($M) | Total Price ($M) | Equivalent 125-UPH Systems | |||

| 12 New Gen II systems | 4.8 | 57.6 | 12 | ||

| 20 Gen I 25-UPH upgrades | 0.6 | 12.0 | 4 | ||

| Total EquipCo proposal | 69.6 | 16 | |||

EquipCo’s proposal delivers the needed sixteen systems’ worth of additional capacity for $69.6M. That is $2.4M lower than the competitor. The customer gets the same capacity, lower acquisition costs, lower facilities cost, commonality, and none of the hassles of changing suppliers. EquipCo gets to keep the customer and protect system pricing. See Figure 56 for this example’s value model.

Rescue a Failed Product Launch with Upgrades

In this example, EquipCo’s newly designed deposition system started shipping at the dawn of a major market upturn. Customers could not get enough of them. In just eighteen months, EquipCo sold eighty units at over $4M each. That was three times more systems than anyone had forecasted. They felt like geniuses.

However, that feeling quickly evaporated as those customers plugged in their new machines.

Once in the customers’ environment, these machines were simply incapable of meeting their yield specifications. They were not even close. None of EquipCo’s customers could use their new $4M machines, and they were furious.

EquipCo’s once frenzied deposition system business came to a screeching halt. They were burning cash so fast that insolvency was a real risk.

Back at headquarters, EquipCo’s engineers figured out what went wrong. There was a fundamental flaw in the system’s source material distribution module. During in-house testing, the engineers missed this flaw because they did not use the same source materials used by EquipCo’s customers. The good news was they had a fix. The bad news was the fix required replacing the entire module to the tune of $100,000 per machine. It was going to take $8M to make their customers whole.

So, the management team called an emergency meeting to figure out how to rescue the business. The meeting started with Bill, Vice President of Engineering, explaining what went wrong and his team’s solution to fix it. When he got to the solution part, Bill let it slip that the fix will also boost the system’s throughput by 25%.

“Wait! Do you mean the new source material distribution module will not only fix the installed-base problem, but it will also improve the system throughput to 25% better than the original specification?” Max, EquipCo’s product manager, asked.

“That’s right,” Bill confirmed.

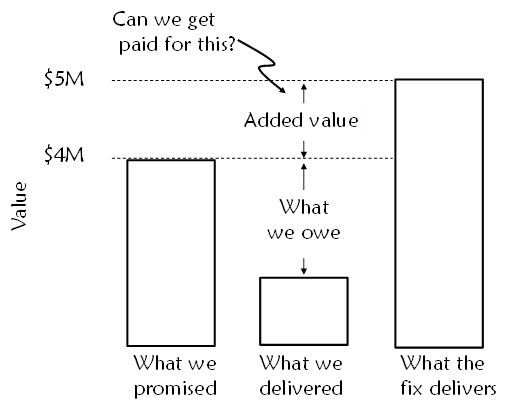

“I have an idea,” Max said. “If I understand our situation correctly, we promised our customers a certain level of value. Then we under delivered by a wide margin. Now we have a fix for the problem that provides 25% more value than our original promise.”

“That’s right,” was the chorus from around the table.

“What if we could get customers the fix and get paid for the value that’s over what we promised?” Max asked.

“How would we do that?” again the chorus.

Max walks up to the whiteboard and draws Figure 57.

Then he says, “Our customers paid around $4M for each machine. The fix that Bill’s proposing increases throughput by 25%. If we had these new modules in the original machine, the machines would have been worth $5M instead of $4M. Let’s tell our customers that we will fix their machines and make them run 25% faster than the original specification at a price that’s a small fraction of this added value.”

“Sounds good when you say it fast,” Bill said. “But there’s no way our customers will go for it.”

Ken, the head of sales, stands. “I think they might. It’s a tough spot for them as well. They have factories full of equipment that does not work. They don’t have the capital or time to scrap it all and start over. They can dig their heels in, but eventually, the rational ones will act in their best interest.”

“Exactly what I was thinking,” Max chimed in. “Our customers need us to do this. I propose we price each upgrade at $175,000. Our customers will get $1M in value above their original purchase at an incredible discount. While they won’t be thrilled about cutting us another purchase order, they will get a fantastic deal. They can get on with running their factories, and we can start rebuilding credibility with our customers. Our message to our customers would go something like this:

‘You will get a completely new source distribution module that will both fix the yield issues you’ve been experiencing and make your equipment run 25% faster than its original specification. The original machines sold for $4M. The 25% productivity improvement makes them worth $5M.

‘We understand that we have seriously disrupted your business, but we cannot afford to upgrade your machines for free. It will bankrupt us. If that happens, we won’t be able to help you recover your investment. The price for this upgrade is $175,000. That is less than 20% of the $1M in value that you will derive from it.’”

Do Not Let Upgrades be an Afterthought

You must plan and develop products with the upgrades business in mind. Equipment companies with a successful upgrades business typically have the following attributes:

- They derive products from a common, multi-generation platform.

- They integrate installed-base upgrade and new product roadmaps.

- Professional product managers manage both systems and upgrade products.

A robust platform strategy is an essential ingredient for capital equipment upgrade business success. A common platform that survives multiple product generations enables you to package capabilities developed for new products into upgrades for the previous generation’s installed base. The longer the platform persists, the larger the upgrade revenue stream. That alone, however, does not ensure success.

The organization must have the discipline to ensure that each new product development program considers making some or all the latest performance capabilities available as upgrades. Designing new features into a new product is easier without backward compatibility requirements. The easy way out is to remove the constraint. However, that forfeits the upgrade revenue stream. You need to weigh the trade-offs between reducing design constraints and maximizing the upgrade business opportunity. Force a return-on-investment review for any potential upgrade that includes:

- Incremental effort and risk of including backward compatibility as a requirement

- The value that the installed-base upgrade would have to your customer and target pricing

- The cost of goods sold for the upgrade

- Total available market for the upgrade and expected revenue capture

- Total potential profit

Next, you need to think about where in the organization to manage the upgrades business.

Sometimes management assigns the upgrades business to the service organization. In capital equipment companies, service groups are fantastic at executing the customer service function. They excel at managing large organizations, moving spare parts, installing systems, rapid response, and controlling complex cost centers. The capabilities needed to develop your upgrades business are different. Upgrade product management is not any different from system product management. Both require the skills to evaluate opportunities, create and capture value, and generate demand. These are the core competencies of your product management team. Manage your upgrades business from there. Plus, you must integrate new systems and installed-base upgrade roadmaps. You have a better chance of achieving that when the same organization manages both.