Table of Contents

- Introduction

- The Customer Defines Value

- Define Your Target Customer

- Value is Relative to the Competition

- Define Your Competition

Introduction

Your product’s value is not:

- Your unique features.

- Your specification advantage.

- The price you need to hit profitability targets.

- Your elegant design.

- Your strong patent protection.

- Your brand.

- Fair compensation for the risk you took and the money you spent developing the product.

It is none of these things. All the above might be your perspective on value. However, your perspective does not matter. It is not about you.

The Customer Defines Value

To illustrate, let us consider two brands of paint on display at your local home center. A quick scan of the small signs hanging below each of them reveals key features for each brand. See Table 7.

| Item | Brand A | Brand B |

| Price/gallon | $25 | $100 |

| Paint lifetime | 5 years | 10 years |

| Total coverage/gallon | 300 ft2 | 300 ft2 |

| Coats needed for complete coverage | 2 | 1 |

Based on the data above, which brand of paint has the superior value proposition?

The correct answer is that you do not know. That is because you know nothing about the customer. The paint’s features do not tell you anything about customer value when you have not defined the customer. Now suppose that the customer is a homeowner. And you know this about the homeowner’s situation:

- The area that needs painting is 3,000 square feet.

- He will pay a contractor $50 an hour to paint his house.

- Each coat will require 10 hours of labor.

- The homeowner expects to stay in this house for more than 10 years.

- He wants the most economical solution for keeping his house looking freshly painted while he lives there.

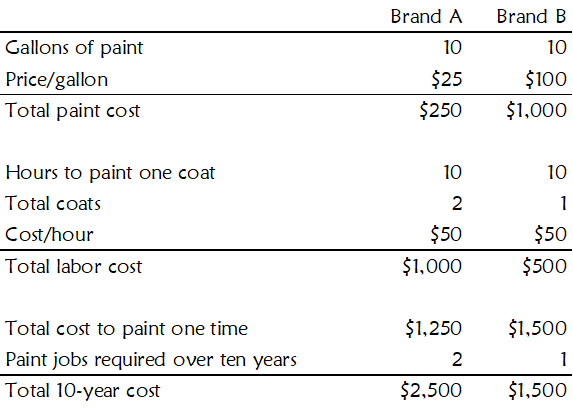

Which paint will produce the most value for this customer? The answer is Brand B. It saves this homeowner $1,000 every ten years with paint lifetime contributing significantly to the buying decision. See Figure 17.

Suppose another homeowner considers the same two cans of paint on the shelf. He, too, wants the best value for his money. His situation is:

- His house has 3,000 square feet of living space.

- A $50-an-hour painter will paint the house.

- The homeowner’s employer is about to relocate him, so he needs to sell his house quickly.

- His realtor told him that a fresh coat of paint would help attract buyers.

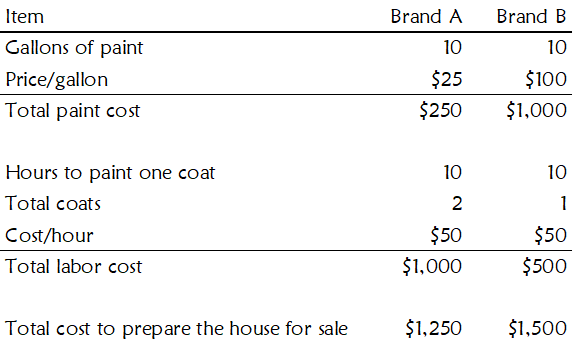

Since this homeowner is only considering the immediate term, paint durability does not matter to his buying decision. Here, the buying decision drivers are paint and labor costs.

By choosing Brand A, this homeowner will save $250. See the value analysis for this homeowner in Figure 18.

From this simple paint example, you can see that you could not define value until you defined the customer. You can also see that a vague description of the customer was insufficient. If you only knew the customer as a homeowner, you would not know enough about him to understand his buying decision drivers.

Define Your Target Customer

You cannot describe value until you define your target market. A precise, accurate definition of value can only come from a precise, accurate definition of the customer. It is the foundation on which you will build your product and marketing strategies.

Defining your target market is the first step. It is a proactive, deliberate, thoughtful decision. You need to select a group of customers:

- With similar buying needs.

- That is large enough to fulfill your financial objectives.

- Whom you will understand as well as you do your own company.

- For whom you intend to create unique value.

Once you have selected your target market, you need to describe it as precisely as possible. Include in your target market description the answers to questions like:

- What types of organizations are in your target market?

- What groups in these organizations will buy from you?

- What job titles do buyers typically hold?

- What are your customers’ products?

- Who are your customers’ customers? (internal/external)

- What are your customers’ customers demanding of them?

- Where are your target customers located?

- Where do they sit in the value chain?

- What problems do they have that you intend to solve?

- What are the requirements for solving these problems?

- How does solving these problems improve their profit?

- What triggers the need to buy?

- How do they make their buying decisions?

- What are their alternatives to buying?

- What are their consequences of not buying?

To test the precision of your target customer description, try this little exercise. Imagine that one thousand people are in the next room, but only five are in your target market. Next to you is a stranger. If you handed that stranger your target market description, could he go into that room and find the five customers that belong to your target market? Once you are confident that he can, you have successfully defined your target market.

Value is Relative to the Competition

Imagine a scenario where you are about to show your equipment proposal to a buyer. You are prepared to defend the $2.8M price circled on the second page. The guys back at the office have role-played the scenario several times. You are ready for anything the buyer throws at you. Just the same, you are a little nervous. Then, just before you slide the proposal across the table and make your pitch, the buyer says,

“This is exciting! Once we get this process up and running, we stand to make $500M more a year in profit.”

You cannot believe what you just heard. You have never heard a buyer make a gaffe like that at the start of a negotiation.

Have you proposed too low of a price? You quickly tuck the proposal back into your folder. There is no way you will let the buyer see it until you add at least another zero.

What if the buyer did not make a gaffe? Sure, he shared the value that equipment like yours has to his business. But is that the same as the value of your equipment?

Suppose the buyer also shares that a competitor has offered to sell them an equivalent piece of equipment for $2M. Now, what do you think tethers your price? The $500M in extra customer profit, or your competitor’s $2M offer?

It is the $2M offer. Your value is relative to the value of market alternatives. Suppose your system produces 1.5 times more value for the customer than your competitor’s $2M system. The full market value of your system is 1.5 times your competitor’s $2M system or $3M.

Pull that proposal back out of your folder and show it to the buyer. Your $2.8M proposal is not a giveaway. It is a defensible value proposition versus your competition.

Define Your Competition

You might think that your competitors are simply the other folks selling equipment like yours. Yes, they are your competitors, but that is not the complete picture. Your competitors come in three forms:

- Direct competition

- Indirect competition

- Decisions to not buy

Direct competition is the obvious head-to-head, equipment-to-equipment competitor. Indirect competition refers to the alternate solutions that your target customer can use to solve their problem.

For example, hard disk drives solve the problem of non-volatile storage for a large volume of data for personal computer users. To the hard-disk drive manufacture, its direct competitors are the other hard-disk drive manufacturers. But alternatives exist where the computer user can avoid buying a large hard drive. They can subscribe to a cloud-based storage service and get away with little local storage. The cloud-based storage service is an alternative solution for the personal computer owner and an indirect competitor to the hard-disk drive maker targeting this market.

The last type of competition, one often overlooked, is the “Decision not to buy.” In the equipment world, the decision not to buy can take many forms, including a decision:

- Not to expand production capacity.

- To repair instead of buying new.

- To operate at a lower yield level.

- To accept lower productivity.

- To endure higher costs.

For example, let us say you have an equipment solution that will improve the yield for a prospect in your target market. That prospect passes on your offer, buys nothing, and continues to run at current yields. Your prospect arrived at that decision by making relative value determination between:

- Do not buy: Avoid new capital investment and live with current yields.

- Buy: Make a capital investment and achieve higher yields.

By choosing number one, the prospect chose your decide-not-to-buy competitor.