Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Not All Equipment is Capital

- The Enterprise vs. the Individual

- Value-Based Strategy Defined

- The Value-Based Strategy Algorithm

- How to Pick Your Value Advantage Target

- Value-Based Price Defined

Introduction

The value that a buyer derives from a purchase can be financial, emotional, or both. Financial factors are simply those that either reduce costs or increase revenue. You can quantify and verify financial factors. You can express them in a spreadsheet. This is not so for emotional factors. They are intangible, subjective, and hard to measure. They include things like prestige, peace of mind, confidence, and pleasure.

Emotions drive many consumer purchases. Sporting event tickets, clothing, snack foods, jewelry, and furniture come to mind. Therefore, consumer product managers must define, create, and market an emotional value proposition.

However, for capital equipment product managers, only financial factors matter. When an enterprise buys a piece of capital equipment, it is buying the one that it believes will produce the best financial outcome. To capital equipment buyers, value is a financial expression.

Not All Equipment is Capital

Capital equipment is any equipment used to provide a service or to make, market, keep, or transport products.

Not all equipment fits the definition of capital equipment above. When it does not, the value-is-a-financial-expression rule does not apply. The distinction lies in how the buyer will use the equipment. See the examples in Table 4.

| Capital Equipment: Value is Financial | Not Capital Equipment: Value is Financial and Emotional |

| A lawnmower purchased by a landscaping company | A lawnmower purchased by a homeowner to mow his own lawn |

| A jumbo jet purchased by an airline | A private jet purchased by a wealthy heiress for travel to exotic vacation destinations |

| A drill press purchased by a machine shop | A drill press purchased by an at-home hobbyist |

| A refrigerator purchased by a restaurant | A refrigerator purchased for a daughter’s wedding gift |

| A high-end gaming computer purchased by a video game production company | A high-end gaming computer purchased by an amateur video game player |

The Enterprise vs. the Individual

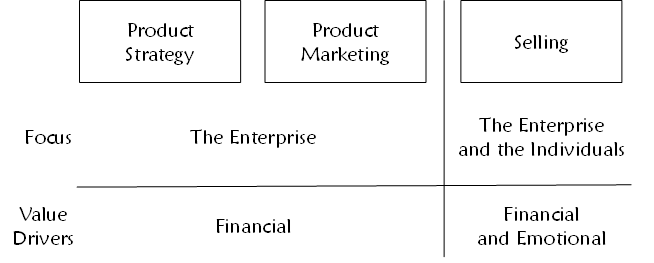

A product manager’s focus is 100% on the enterprise. Your mission is to define, create, and market products that produce more financial value than the alternatives. Not so for the salesperson. He or she must substantiate your equipment’s financial value to the enterprise and address the emotional needs of the individuals taking part in the purchasing decision. See Figure 14.

When you are selling capital equipment, you are selling to an enterprise. For the enterprise, only economic value drivers matter. The enterprise does not have feelings.

However, the individual in the enterprise does have feelings. That individual may need to feel secure that his equipment purchase decision will not put his job at risk. Or he may need to prove that he is a tough negotiator to earn the boss’s respect. Individuals can satisfy an overwhelming portion of their emotional needs by looking after the economic needs of the enterprise. By consistently making decisions that lead to higher profit for their employer, individuals can expect to feel secure, appreciated, and respected. But you cannot expect that the enterprise and the individual needs are always the same.

For example, suppose an individual bought your competitor’s equipment the last time he purchased. This time around, he has changed his mind and wants to buy yours. However, he is worried that doing so will appear as an admission that his previous decision was a mistake. This individual has an emotional need to appear competent in both decisions.

Value-Based Strategy Defined

Put your management team in a room. Then, ask them what they want out of a value-based strategy. You will get a chorus of something like:

“More customers at higher prices.”

Seems everyone knows exactly what they want from a value-based strategy.

Now imagine that same exercise. Only this time, you ask them, “What is a value-based strategy?” This time, instead of a chorus, you will get a cacophony of ideas like:

- Value

- Customer

- Cost of ownership

- Products

- Features

- Performance

- Competition

- Price

- Cost

- Selling

- Profit

- Economics

- Difficult

- Strategy

- Market

All these are part of a value-based strategy. But what you are looking for is a clear, holistic definition that you can use to guide the organization’s value-based strategy decision making and implementation. If you were to ask the group to summarize these ideas into key themes, you would get something like:

- Economic value for the customer

- More value than the competition

- Fair, profitable compensation

- Deliberate

These themes tell you a lot about capital equipment value-based strategy. Let us tie it all together.

Economic Value for the Customer

This value-strategy theme tells you that the customer defines value. Therefore, you will need to define that customer clearly. Market segmentation will not be an off-the-cuff decision. Also, capital equipment buyers only buy to make a profit. Profitability is the lens through which they define value. If you intend to pursue a value-based strategy, you will need to understand how your equipment affects your customers’ economics.

More Value than the Competition

Your customers measure your value relative to the alternatives in the market. A value-based strategy seeks to create more value than those alternatives. Your competitive intelligence efforts will need to go beyond reading competitors’ websites and reviewing stale win-loss reports. You must develop a deep understanding of your competitors’ ability to create value.

Fair, Profitable Compensation

As an equipment supplier, you are entitled to a portion of the value that you provide your customers. Fair compensation is the maximum that the market will bear in your competitive environment. A value-based strategy is interesting only if it enables you to make more profit. Therefore, your products must produce acceptable profitability when you sell them for fair compensation.

Deliberate

Consistently achieving the returns promised by a value-based strategy is not an ad hoc endeavor. It is a deliberate decision to make defining, creating, and communicating customer value a core competency. The decision to adopt a value-based strategy is going to have a profound effect on the way you define, develop, market, price, and sell your equipment. There is nothing casual about it.

Put these four themes together, and you a get value-based strategy definition with everything you need to guide your product strategy and marketing.

A value-based strategy is a product and marketing strategy that deliberately creates more financial value for the target customer than alternative offerings and then extracts fair, profitable compensation for that value.

The Value-Based Strategy Algorithm

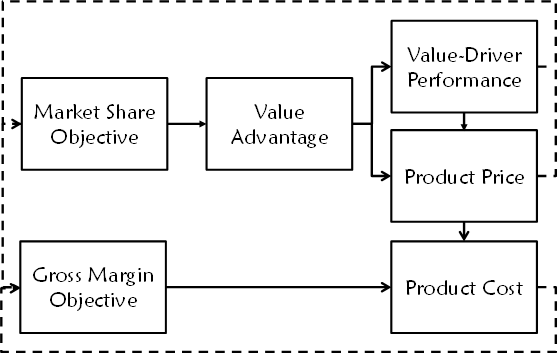

An algorithm is a formula for solving a problem. Defining a feasible value-based strategy is the problem you need to solve. To solve that problem, you need an algorithm that reconciles the trade-offs among market share objectives, gross margin objectives, value advantage targets, value-driver performance, product price, and product cost.

See the value-based strategy algorithm in Figure 15 and the description of its variables in Table 5.

| Value-Strategy Element | Description |

| Market share objective | Percentage of the market management intends to capture with the product |

| Value advantage | Added value vs. the competition needed to achieve the desired market share expressed as a percentage |

| Value driver performance | Product performance on those attributes that either reduce costs or increase revenue |

| Product price | The amount a customer pays for your product |

| Product cost | The supplier’s cost to produce the product |

| Gross margin objective | The level of profitability management desires for the product |

The algorithm solves two simultaneous equations that share the same value for the product price. Algorithm elements two through four make up the first equation. It produces a product performance and price scenario that results in a value advantage, which drives market share. Elements four through six make up the second equation. It generates a price and cost scenario that results in gross margin.

The algorithm’s solid lines show the logic that forms a value-based strategy. The dashed lines pay homage to the iterations needed to find a solution that produces the required customer value at acceptable profitability.

All the value-based strategy algorithm variables must reconcile. You cannot change one without having it affect at least one other element in the algorithm.

For example, suppose midway through a product development program, you learn the team will not achieve a key value driver’s performance target. For the algorithm to reconcile, you must do one of three things:

- Increase the performance of one or more other value drivers to produce the original target value.

- Lower your target value advantage. This preserves unit profitability but reduces the expected market share.

- Lower the price. When you lower the price, you must also lower the gross margin or the product cost target.

As another example, imagine a customer has committed to buy from you if you can deliver a 20% value advantage. Then in the final innings of a sales negotiation you learn that your value advantage over your competitor is smaller than you thought. Assuming that you cannot change product performance and cost, you have two choices:

- Lower your price, achieve the 20% value advantage, and win the order at a lower gross margin.

- Lose the order and miss your market share objectives.

How to Pick Your Value Advantage Target

A universal formula to calculate the market share change rate from a value-advantage percentage does not exist. The number of customers, customers’ buying frequency, sales cycle length, the cost of changing suppliers, and other factors vary widely across equipment market segments. To develop a mathematical formula, you would have to model historical share-shift behavior as a function of these variables for your market segment. This is not practical or necessary.

However, you can conclude a large value advantage will produce a faster market share increase than a small one. See Table 6 for some market and competitive situation examples.

| Situation Example | Value Advantage Implication |

| You are the incumbent supplier with 100% market share. | You will not need a large value advantage to hold your position if the cost of changing suppliers is high. |

| You are targeting a new emerging market where greenfield opportunities dominate. | Since there are no incumbents, the cost-of-change factor is irrelevant. You will gain market share anytime your value is greater than that of your competitor. |

| You are an established player trying to dislodge a competitor that holds 100% market share. | Your value advantage must be large enough to overcome your target customer’s cost of changing suppliers. |

| You are a higher-performing new entrant looking to capture market share from a well-established competitor. | Despite your value-driver performance advantages, your target customers may be reluctant to buy from an unproven supplier. An exceptionally large value advantage may be necessary to attract your competitor’s customers. |

Value-Based Price Defined

A value-based price is the highest price you can charge relative to market references for your added value and still achieve your market share objectives.

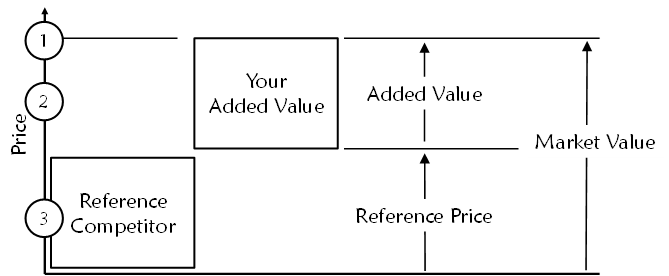

See the simple, value-based pricing diagram in Figure 16.

In this diagram:

- The height of the box labeled “Reference Competitor” refers to the price of your customer’s next best alternative.

- The height of the “Your Added Value” box is the value your solution produces for the customer above the reference competitor’s value.

- The total height of the “Reference Competitor” and “Your Added Value” boxes is the price of your solution at full market value.

- The price axis is the range of all prices you could set for your product.

The three pricing levels shown in the diagram are the:

- Price at full market value

- Price higher than the reference competitor’s price but below full market value

- Price at or below the reference competitor’s price

The right level for your value-based pricing will depend on the value your solution produces for the customer and your market share objectives.

When you price your equipment at full market value, the customer’s financial outcome is the same, whether he buys from you or the reference competitor. Your customers and your competitor’s customers would likely remain with their current supplier. You would not gain or lose market share. This might be the right price for you if you are already the undisputed market share leader and have no ambition to capture new customers.

Pricing higher than the market reference price but below full market value can produce market share gains. Your value advantage just needs to be sufficient to attract your competitors’ customers.

Pricing below the market reference can also be a rational value-based price in a couple of situations. One being your product performs the same or worse than the reference competitor on the most important value drivers. Therefore, you need to compensate with a lower price. The second is the case where, despite a value-driver performance advantage, you need to offer an impossible-to-ignore value proposition to attract your competitors’ customers. These scenarios illustrate that value-based pricing can be any price that is a function of the value your solution produces for the customer and your market share objectives.